My Home is on the Mountain

About the Book

For those readers who want to know more about the book, I offer the background to all the references in the text of the story, including the music played, the history of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, places, and so on. I hope it will be interesting to those who want to know more about the things I mention. When I want to give a deep dive into a subject, I have put it in a drop-down box, so those who don't want to go that deeply can just skip over.

About the Book's Title

MY HOME IS ON THE MOUNTAIN is set in eastern Tennessee, specifically, the Great Smoky Mountains and the rolling ridge and valley country to their west.

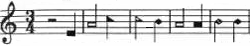

The title comes from a very old song. I learned it as a child from a little book of American folk songs. I found references tracking it back to the 1700s in England. This reference book on Catskills folk songs lists it and traces variant tunes back even further, to the Middle Ages. My research showed me that the lyrics had often been changed to suit the times; certainly the version I learned as a child was clearly re-written to be a Civil War song, but the line "My home is on the mountain" has endured in the same place (third line, first verse) from the very earliest examples. I have loved this song all my life, and one day, while singing it aloud, I realised that I was singing the title of this book.

Chapter One

The story opens on Friday, 5 June 1931. Cecilia Howison is stranded on a high mountain road. She drove back from tending her great-aunt's grave on a hot day, and turned up a forest road that looks like it might take her higher to cool breezes. She has not been this high into the mountains before and is starting to realise that she might be on a road that leads nowhere. Then her car overheats and she pulls over as clouds of steam erupt from the vents of her car's hood.

Cecilia drives a 1929 Buick Roadster, specifically, the Master Six Sport Roadster, which was a two-seater with what we would call now a rumble-seat (then the "rear deck") that seated two more. What we refer to now as running boards were called side-mounts. Watch a slideshow of a cream-coloured 1929 Buick roadster with caramel leather. Gorgeous.

Cecilia drives a 1929 Buick Roadster, specifically, the Master Six Sport Roadster, which was a two-seater with what we would call now a rumble-seat (then the "rear deck") that seated two more. What we refer to now as running boards were called side-mounts. Watch a slideshow of a cream-coloured 1929 Buick roadster with caramel leather. Gorgeous.

Cecilia's roadster was custom-ordered for her, because her family is that rich. Hers is light blue with cream leather upholstery. Roadsters were small cars, very snug. This colour image of the 1929 Buick shows a beautifully restored model with the rear outside seat opened (I have altered the photo here to the shade of blue and with the cream leather of Cecilia's own car). These roadsters were designed as powerful sports cars, built for those who liked to drive a superior machine and who wanted to go fast, which is Cecilia in a nutshell.

Cecilia's roadster was custom-ordered for her, because her family is that rich. Hers is light blue with cream leather upholstery. Roadsters were small cars, very snug. This colour image of the 1929 Buick shows a beautifully restored model with the rear outside seat opened (I have altered the photo here to the shade of blue and with the cream leather of Cecilia's own car). These roadsters were designed as powerful sports cars, built for those who liked to drive a superior machine and who wanted to go fast, which is Cecilia in a nutshell.

I want to stress that overalls worn back then were designed to protect the clothing underneath, and so they would provide a sufficiently modest covering for a naked girl. The sides where higher under the arms than modern "slouch" overalls and, as you can see, the bib was up high, just under the collarbones. During her first conversation with Airey Fitch, Cecilia plays with a stem of blue-eyed grass. Such a prosaic name for a beautiful flower, which thrives in mountain meadows. As they sit and talk, they are framed by a froth of wildflowers.

I want to stress that overalls worn back then were designed to protect the clothing underneath, and so they would provide a sufficiently modest covering for a naked girl. The sides where higher under the arms than modern "slouch" overalls and, as you can see, the bib was up high, just under the collarbones. During her first conversation with Airey Fitch, Cecilia plays with a stem of blue-eyed grass. Such a prosaic name for a beautiful flower, which thrives in mountain meadows. As they sit and talk, they are framed by a froth of wildflowers.

As Cecilia drives away from her first meeting with Airey, she thinks of a flash-lamp as a metaphor. While flash-lamps using flash-bulbs had been invented in 1927, Cecilia would have been more familiar with powder flash-lamps, still in use by many newspaper photographers, which were narrow horizontal containers that held flash-powder. This was ignited by a spark and gave a quick, blindingly-bright flash of light. The development of flash photography (video).

As Cecilia drives away from her first meeting with Airey, she thinks of a flash-lamp as a metaphor. While flash-lamps using flash-bulbs had been invented in 1927, Cecilia would have been more familiar with powder flash-lamps, still in use by many newspaper photographers, which were narrow horizontal containers that held flash-powder. This was ignited by a spark and gave a quick, blindingly-bright flash of light. The development of flash photography (video).

Cecilia returns home, and here we meet several of the staff who are employed by her parents. There is no getting around the fact that in 1931 in eastern Tennessee, the servants of the very wealthy, including Cecilia's family, would have servants who were African-Americans. I set this novel in the real South, and if I was going to show poor mountain people as they were, I had to show the rich as they were. I did a lot of reading, and I strove for a two-layered view, so that the limitations of choices and actions for the African-Americans working for the Howisons would be plain enough to the reader, even while the white characters around them miss this or do not care about this. I was wary of the myths peddled, at that time (and, shockingly, still now), that there was some sort of friendly, co-respectful interdependence of white and Black. I was also aware that Knoxville, which I used as my starting point for Charleville, had a thriving and politically-active Black community and business sector, and those voice could not be ignored. See more on this informative East Tennessee History website. Nevertheless, Jim Crow was always lurking, and violence or the threat of violence against African Americans was a constant reality.

African Americans in Tennessee

Almost all the staff and servants in the homes of rich white Southerners were African-American, and most of these people were descendants of the enslaved people brought to what had been the original plantations. The relationship of African-American staff to their employers was always complex, and never what the white employers thought it was. White people saw their servants as loyal, sometimes even "part of the family" (but not the part that get to sit down at the Thanksgiving dinner table). The African-American employees did not share this view.

African-Americans originally came to what is now Tennessee by two routes. First, some among those who were enslaved in the thirteen colonies escaped, slipped over the mountains, and settled with, or among, the indigenous peoples. Second, they were brought in as chattel slaves. (There were indeed a very few Free Blacks, but let us concentrate on the vast majority.) These enslaved people worked every place that profited by expendable, cheap labour: on farms and in the farm houses as house-slaves, working as loaders and crew on the rivers, dealing with livestock, down in the mines, in road-building, logging, and so on. After the Civil War, this work did not change much, except that now African-Americans had other choices, from teacher and lawyer to newspaper reporter to doctor to pharmacist to factory worker.

Nevertheless, their freedom of action and choice were always grotesquely limited by racism. Knoxville had a large African-American community, with newspapers and active political groups. The city was seen as very tolerant, and yet there were race riots against African-Americans and of course restrictions everywhere.

I am not going to attempt a detailed history here; this can be found in many books and websites and museums. And of course it is not just history. My reference sources can be found in my bibliography. Tennessee's capitol still has less than ten years ago removed a statue to Nathan Bedford Forrest, the vicious, rabid, and racist Confederate officer and founder of the KKK. Not erected in the 1920s or 1930s, but in 1978. And yet a much better monument to everything Forrest stands for already exists: Fort Pillow.

That evening, Cecilia plays music for her family. Cecilia has already mentioned, when talking to Airey, that she plays the piano. She is modest about her ability, but in fact she is a very good amateur pianist. She first plays Ignaz Moscheles' piano études. These are charming short pieces, very much composed as easy listening at the time of composition and they remained so even up to Cecilia's day. They fell from favour, but now are seeing a small revival. Enjoy three of them in this video (YouTube). Cecilia then moves to Schubert's Moments Musicaux aka "Musical Moments." Today, Schubert's solo piano works are concert pieces, but then, most of his piano pieces were seen as fit only for amateurs. Enjoy Schubert: Moments Musicaux played by Alfred Brendel (YouTube). because how could you not?

The next day, Cecilia drives into Avender. This small town is situated roughly where the real Maryville sits, but is mostly definitely not the real town in disguise. The name "Avender" comes from one of the volunteers who fought at the Battle of King's Mountain in the American Revolution. More about the Battle of King's Mountain.

In the music store, Cecilia buys a book that actually existed. She has recently been a music student and isn't ignorant about the violin, but wants to brush up. She goes to the soda fountain in the drug store. Soda fountains in drug stores were not only seen as "chemical" and so somehow medical (because of all that health-giving cream, sugar, and soda water, naturally), but were also a good draw to get customers through the doors. Cecilia's cherry phosphate was not just cherry syrup in soda water. More info.  The movie she sees with Patmore is a real movie that was showing in 1931. It had been released a little before June, so was not fresh off the griddle. While the feature film normally changed once a week in movie houses, slightly older films continued to circulate to smaller cities and towns, and I found movies released months earlier still being listed in local town papers. The Good Bad Girl sounds like a dog. Read a review. Cecilia mentions Ginnie Moon. She really was a "girl spy," being 16 when she started. I have zero admiration for or interest in the Confederacy, but Cecilia would have grown up on the stories about it, and clearly liked the idea of a girl who hid the truth and had secrets. If you want to know more about Ginnie Moon, be my guest.

The movie she sees with Patmore is a real movie that was showing in 1931. It had been released a little before June, so was not fresh off the griddle. While the feature film normally changed once a week in movie houses, slightly older films continued to circulate to smaller cities and towns, and I found movies released months earlier still being listed in local town papers. The Good Bad Girl sounds like a dog. Read a review. Cecilia mentions Ginnie Moon. She really was a "girl spy," being 16 when she started. I have zero admiration for or interest in the Confederacy, but Cecilia would have grown up on the stories about it, and clearly liked the idea of a girl who hid the truth and had secrets. If you want to know more about Ginnie Moon, be my guest.

Cecilia's first trip back to the mountains to meet Airey again requires her to drive up the slopes of a high mountain, called Applesell Bald. A "bald" is indeed a bald mountain, that is, a forested mountain whose summit is grassy with, at most, low scrub, but without trees. It is a natural occurrence. Just as drovers still do in the mountainous parts of Europe, settlers drove their beasts up in the summer to feed on the rich high meadows, and if a mountain bald was tempted to reforest, this annual grazing would have discouraged it. In 1931, herds were no longer taken up the mountain, and the track Cecilia is on has deteriorated. As Cecilia finds out.

Cecilia's first trip back to the mountains to meet Airey again requires her to drive up the slopes of a high mountain, called Applesell Bald. A "bald" is indeed a bald mountain, that is, a forested mountain whose summit is grassy with, at most, low scrub, but without trees. It is a natural occurrence. Just as drovers still do in the mountainous parts of Europe, settlers drove their beasts up in the summer to feed on the rich high meadows, and if a mountain bald was tempted to reforest, this annual grazing would have discouraged it. In 1931, herds were no longer taken up the mountain, and the track Cecilia is on has deteriorated. As Cecilia finds out.

She finds Airey away, scything one of the meadows on the farm. This is a job done best in the early morning. The work is beautiful to watch, but scything a large field all morning, only stopping to sharpen your blade every few minutes, was hard labour. If you want to see a scyther in action, I offer a video of a young woman mowing a very big field. Its intro is a bit odd and the video is silent. You might want to skip the first 2:15 minutes. Then just watch her mow, mow, sharpen her scythe, mow (YouTube). The woman in the video is barefoot, but scything risks the feet. Airey wears boots.

When Airey returns, she compares Cecilia to a nuthatch. I offer a photo of a white-breasted nuthatch to give a hint of the lovely colours of Cecilia's frock. It is this dress that Cecilia's friend Patmore complimented in the previous chapter, comparing her to a hyacinth. Airey is more accurate.

When Airey returns, she compares Cecilia to a nuthatch. I offer a photo of a white-breasted nuthatch to give a hint of the lovely colours of Cecilia's frock. It is this dress that Cecilia's friend Patmore complimented in the previous chapter, comparing her to a hyacinth. Airey is more accurate.

The Fitch house is a wooden frame house, not a log cabin. The image here is an old house very similar to it in general layout. The chimney of the Fitch house is at the rear, not at the side. The Fitch farmhouse's rear spur is more off-centre and is a saddle-bag log cabin (two small cabins joined by one roof, with a stone chimney shared between them and usually with a sheltered area in front of the chimney) against one end of which the new frame house was built, by removing the end log-wall of the older house and connecting them. The house in the photo is surrounded by trees; the Fitch house has flowerbeds and an open yard around it and is set on the steep slope of a mountain right by a small, swift stream.

The Fitch house is a wooden frame house, not a log cabin. The image here is an old house very similar to it in general layout. The chimney of the Fitch house is at the rear, not at the side. The Fitch farmhouse's rear spur is more off-centre and is a saddle-bag log cabin (two small cabins joined by one roof, with a stone chimney shared between them and usually with a sheltered area in front of the chimney) against one end of which the new frame house was built, by removing the end log-wall of the older house and connecting them. The house in the photo is surrounded by trees; the Fitch house has flowerbeds and an open yard around it and is set on the steep slope of a mountain right by a small, swift stream.

A griffin (or gryphon) is a mythological creature, combining the bodily parts and attributes of a lion and an eagle, being regal and powerful, intelligent, bold, and graceful. It represents loyalty and courage. It protects gold, heals blindness, and mates for life. It is a symbol of the sun.

Airey sands her hands when she is about to play the fiddle, as her sister Merit explains to Cecilia. Airey uses feldspar, which was available locally. She was given a small sack of it from a neighbour who had been over in North Carolina. Two books in my bibliography mention using feldspar on the hands, one nearly contemporaneous to the time of the novel: (Sheppard).

Airey does not use either a chin-rest or a shoulder-rest on her violin. Chin-rests were not common in her time, and the shoulder-rest was unknown. The latter only slowly became common toward the end of the twentieth century. If you'd like to learn more, here is an interesting video on why you should not use a shoulder-rest (YouTube).

Fiddle contests exist then as now throughout not only the American South, but all across North America. Many were and are very local, perhaps strictly within a county, but some, in these early days of radio, could lead to both fame and money. Airey plays not just old-time music for Cecilia, but music from a wide range of sources.

The music at the kitchen door

Airey begins with In the Gloaming a song written in the 1877 by a woman composer, with a woman lyricist. It is hard to find an accurate version of the original song, although I myself grew up singing it, because a 1910 recorded version featured a cut-down travesty of the song, presumably to fit the size of disc then available, and that became the known version. Ignore every link Wikipedia offers!! The full original verses (it isn't a long song) carry much more meaning than the crass bathetic 1910 version, which you can find all too easily online. I don't recommend it. This, below, is the only one I have found that gives the entire original song with almost all the original words (a few are changed, but the meaning is not). If you find a version just over two minutes long, it is the yucky cropped version. The reason I am so vehement is that (1) the short versions ruin the meaning of the actual song and (2) that original meaning is core to my novel. Here is a version to give you an idea of what Cecilia hears Airey play:

In the Gloaming, by Annie Fortescue Harrison, lyrics from poem by Meta Orred, sung and played by Boxer John:

(Give his Vimeo video of this a boost by listening to it there.)

Violin solo: In the Gloaming, played by Johann Beavis Berry:

Airey moves to other music. It's hard to find early recordings that feature solo fiddle. I include a few here, as examples of the music Airey would play. They are not good audio quality, as they were taken from the original shellac records. The same quality warnings are for the examples of other popular music I offer here, not played by solo violin, so do your best to imagine how Airey would have transcribed them.

Sail Away Ladies, played by Uncle Bunt Stephens (recorded in Tennessee in 1926):

Bunt Stephens was an eastern Tennessee fiddler and I think he is magnificent. He made two records, that is four songs, after winning a fiddle contest.

Fiddlin' John Carson was a fiddler from Georgia. This recording is pretty scratchy:

Billy in the Low Ground, played by Fiddlin' John Carson (recorded 1924):

Other music played by Airey (all these recordings are scratchy to a degree):

Grey Eagle, played by Uncle Am Stuart (recorded 1924):

Bonaparte's Retreat, played by A. A. Gray (recorded 1924):

Sallie Gooden, played by Eck Robertson (recorded 1922):

Mountain Hornpipe, played by Jehile Kirkhuff (recorded in 1950s):

Kirkhuff was recorded in the 1950s and later. He is an example of the Pennsylvanian fiddle tradition.

Fisher's Hornpipe, played by Henry Reed (1966) [Link takes you to the U.S. Library of Congress website.] Reed, a Virginian fiddler, was 82 when he was recorded; he would have been in his late 30s at the time of my novel.

Airey then moves to other popular music of the time.

Kohala March, played by Franchini and Dettborn (recorded 1920):

An example of the "Hawaiian music" popular during the 1920s. Try, if you can, to imagine this being played on a fiddle.

A Precious Little Thing Called Love, played by George Olsen and His Music [i.e. his band] (recorded 1929):

I can imagine Airey having fun with this melody.

Sleepy Time Gal, played by Bern Bernie and his Hotel Roosevelt Orchestra (recorded 1926):

Sorry about the sound quality. Yet another recording to test your audio imagination, as you try to hear this played by a single fiddle.

After the Ball, played by the International Novelty Orchestra (recorded 1925):

This starts as an instrumental version, so easier (I hope) to hear it as a single violin.

Bambalina, played by Carl Fenton (recorded 1923):

A dance tune very popular through the 1920s.

Ain't She Sweet, sung by Gene Austin (recorded 1927):

Austin has quite a voice. Today, this song could be seen as just a little creepy, but my grandmother sang it to me and nobody raised an eyebrow at the lyrics. Still, it's a great tune.

It All Depends on You, played by Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra (recorded 1927):

Paul Whiteman was a serious star in the 1920s and popularised much African-American music, safely adjusted for his own audience, as well as music like this.

My Heart Stood Still, sung by Melville Gideon (recorded 1927):

I chose this version for the snippets of violin included in it.

To close off these examples, I jump back to old-time music, as Airey does to end this part of her show.

Soldier's Joy, played by Luther Strong (recorded 1937):

This old-time reel, played by an elderly man who would have been playing this from the earliest days of the 20th century, ends this set of examples of the range of music Airey plays for money.

Now Airey changes musical direction and plays something very different.

Bach: Preludio, from Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin, played by Hilary Hahn:

Airey is a very young woman in the story and Hilary Hahn recorded this when she was, too. Quite often violinists have a tiny pause about four seconds in, because the bowing and fingering is difficult, but Hahn simply glides through it (as does Rachel Barton Pine, below, as does Airey).

Rachel Barton Pine has an amazing, beautiful version. I know I shouldn't have favourites, but holy smoke:

Bach: Preludio, from Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin, played by Rachel Barton Pine:

Airey then plays the rest of the pieces that make up this suite. I offer two versions of the next piece, the Loure.

Bach: Loure, from Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin, played by Hilary Hahn:

I've chosen the musicians here throughout because they play the modern violin, not the baroque version, as the baroque violin had not been revived in Airey's time and would not be until four or five decades later, and I personally have zero problem with Bach played on a modern instrument.

Rachel Barton Pine plays the Loure with touches of French-style decoration, which is absolutely of the time of composing, but Airey would not have known that this was allowed.

Bach: Loure, from Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin, played by Rachel Barton Pine:

The Loure is followed by the Gavotte en Rondeau.

Bach: Gavotte en Rondeau, from Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin, played by Augustin Hadelich:

I always think this is my favourite bit of the entire suite until...

Bach: Menuetts I and II, from Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin, played by Midori Goto:

The minuets are nested, II inside I, and so I think they should be played together rather than split, which adds a pause in recordings where no pause should be. I've chosen Midori Goto's version because I wanted to offer an older virtuoso playing from a lifetime of experience. She, like Barton Pine, adds in a few lovely touches. I absolutely love these two minuets. I would probably die for them.

I can't help slipping that Rachel Barton Pine here. Her Menuets are again beautifully, indeed ravishingly, decorated with little French touches that charm my heart.

Bach: Menuetts I and II, from Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin, played by Rachel Barton Pine:

The Bourrée is played faster nowadays than it was in Airey's time. Back then, this would have been a typical approach:

Bach: Bourrée, from Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin, played by Henryk Szeryng:

Bach's Third Partita ends with a jig, spelled Gigue, and here it is, played with exemplary clarity:

Bach: Gigue, from Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin, played by Julia Fischer:

If you want to know more about this partita, and also want to see how a violinist approaches a score and makes musical decisions on how to play it, Rachel Barton Pine offers a series of YouTube master-classes. She is playing with a modernised baroque violin and bow. Her talks through each piece are both illuminating and exciting, for you see her thought, respect, pleasure, and delight in the music. Here is her discussion of the Preludio (YouTube), and the rest follow.

You can also buy Barton Pine's complete set of solo violin sonatas and partitas, and why wouldn't you have these in your life? Honestly, played by any leading violinist (but especially Barton Pine), these six suites are music that would sustain you on a desert island for one hundred years and you would still listen with joy and be refreshed in year 100.

There is a reason Cecilia leaps to her feet when Airey begins to play Bach.

Having heard Airey, Cecilia rushes home. She plays some of Bach's English Suites on the piano as she thinks about what she can do for her. You can hear all the English Suites played by Murray Perahia (YouTube). Again, Cecilia is not the so-so pianist she claims, since she can play these suites. Babbitt was best-selling novel by Sinclair Lewis published in 1922, and which gave the English language a word for a philistine who does not have an aesthetic bone in his body (I simplify). Glass puzzles still exist, and they are still hard to solve.

Having heard Airey, Cecilia rushes home. She plays some of Bach's English Suites on the piano as she thinks about what she can do for her. You can hear all the English Suites played by Murray Perahia (YouTube). Again, Cecilia is not the so-so pianist she claims, since she can play these suites. Babbitt was best-selling novel by Sinclair Lewis published in 1922, and which gave the English language a word for a philistine who does not have an aesthetic bone in his body (I simplify). Glass puzzles still exist, and they are still hard to solve.

Cecilia makes a second visit to the music shop, where she buys a number of records. Records then could only take about three minutes of music on each side. Songs could fit this limited space, but longer pieces of music had to be spread over a number of records. Records were made of shellac resin and were brittle as ice. They were slipped into paper sleeves to protect them. Albums were simply books of bound empty sleeves where collections of records could be kept together.

Cecilia makes a second visit to the music shop, where she buys a number of records. Records then could only take about three minutes of music on each side. Songs could fit this limited space, but longer pieces of music had to be spread over a number of records. Records were made of shellac resin and were brittle as ice. They were slipped into paper sleeves to protect them. Albums were simply books of bound empty sleeves where collections of records could be kept together.

Chapter Two

Cecilia returned to the mountains in the most achingly fashionable of clothes, that is, what she usually wears. I offer an image of a postillion cap, worn by the Hollywood star Carole Lombard in 1932, that is, a year later, i.e. she is eating Cecilia's dust.

Cecilia returned to the mountains in the most achingly fashionable of clothes, that is, what she usually wears. I offer an image of a postillion cap, worn by the Hollywood star Carole Lombard in 1932, that is, a year later, i.e. she is eating Cecilia's dust. Cecilia encounters Airey's younger brother, Lorimer, and Lorimer's dog, Royal. Royal is a feist dog, a breed of small dog about the size of a terrier, bred for hunting, especially squirrel-hunting. [More on the feist dog breed.]

Cecilia encounters Airey's younger brother, Lorimer, and Lorimer's dog, Royal. Royal is a feist dog, a breed of small dog about the size of a terrier, bred for hunting, especially squirrel-hunting. [More on the feist dog breed.] Cecilia arrives again at the Fitch house. Cecilia comes from a family that upholds older values, both good and bad, including an adherence to an old-fashioned etiquette. On her first trip, she brought for Airey's mother a small hostess gift, and now leaves a visiting card. These were not business cards, but simply cards roughly that same size, a bit more square, with simply your name on it, that you could drop off to show that you had called. You could add a note to it, as Cecilia does.

Cecilia arrives again at the Fitch house. Cecilia comes from a family that upholds older values, both good and bad, including an adherence to an old-fashioned etiquette. On her first trip, she brought for Airey's mother a small hostess gift, and now leaves a visiting card. These were not business cards, but simply cards roughly that same size, a bit more square, with simply your name on it, that you could drop off to show that you had called. You could add a note to it, as Cecilia does.

Mrs. Grigg, Airey's mother, mentions an old-time string band called the Melodious Mountaineers. This name is similar to many names such bands gave themselves in the 1920s, such as The Skillet Lickers. Old-time bands adopted these pejorative names both to flag the type of music they played and, as African-American players had to do, to make themselves more acceptable to a prejudiced potential market. Other bands stuck to names such as Taylor's Kentucky Boys and The Carter Family.

A "stack cake" (or "stack pie") is a number of pies stacked up on each other as if they were a layer cake. The pies can be all one flavour, for instance, three or four apple pies, or pies with various fillings. A recipe and photo of a stack cake.

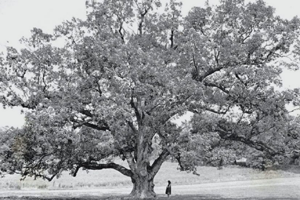

When Pastor Souch arrives to see Mrs. Grigg, he speaks of the chestnuts on the Fitch farm. I can do no better than to quote from The American Chestnut Foundation: "More than a century ago, nearly four billion American chestnut trees were growing in the eastern U.S. They were among the largest, tallest, and fastest-growing trees. The wood was rot-resistant, straight-grained, and suitable for furniture, fencing, and building. The nuts fed billions of wildlife, people and their livestock. It was almost a perfect tree, that is, until a blight fungus killed it more than a century ago. The chestnut blight has been called the greatest ecological disaster to strike the world's forests in all of history." (Source: ACF.org). Chestnuts were first noticed suffering from, and dying from, this fungus in 1904. These huge trees, often 100 feet tall, were nearly wiped out. By the late 1920s, even the remote vales and slopes of the Appalachias were losing their chestnuts at a frightening rate. At one point it seemed that the United States would entirely lose this glorious tree. Luckily, some have survived, and you can help fight for their future by donating to the ACF.

When Pastor Souch arrives to see Mrs. Grigg, he speaks of the chestnuts on the Fitch farm. I can do no better than to quote from The American Chestnut Foundation: "More than a century ago, nearly four billion American chestnut trees were growing in the eastern U.S. They were among the largest, tallest, and fastest-growing trees. The wood was rot-resistant, straight-grained, and suitable for furniture, fencing, and building. The nuts fed billions of wildlife, people and their livestock. It was almost a perfect tree, that is, until a blight fungus killed it more than a century ago. The chestnut blight has been called the greatest ecological disaster to strike the world's forests in all of history." (Source: ACF.org). Chestnuts were first noticed suffering from, and dying from, this fungus in 1904. These huge trees, often 100 feet tall, were nearly wiped out. By the late 1920s, even the remote vales and slopes of the Appalachias were losing their chestnuts at a frightening rate. At one point it seemed that the United States would entirely lose this glorious tree. Luckily, some have survived, and you can help fight for their future by donating to the ACF.

When Pastor Souch has left, Airey's mother speaks of her own future and the future of the farm, and Cecilia understands very well what Mrs Grigg is talking about, because the coming of the national park in the Great Smoky Mountains was a contentious and expensive project, much discussed everywhere and by all. See below for more information on the national park.

Mrs Grigg cooks the main meal of the day, including spoon bread. Here is a spoon bread recipe. She sings while she cooks, to Cecilia's pleasure, and I quote the actual lyrics of a Sacred harp (shape-note) song: 301 Greenland.

About Sacred Harp singing

Shape-note, also called Fasola (from the first three notes: fa, so, la), which are also, more recently, are called do, re, mi) has an old history, and may stretch back to the poor rural Protestant peoples of the Border Country in England and Ulster. Another line of research suggests that it first came to New England and then spread south. It became visible to history with the publication of song-books, the most famous being The Sacred Harp, a commercial publication that became extremely popular, and which gave its name to this style of singing. It had many editions. The publishing company did much to spread the habit of shape-note singing, for this increased their own sales. They eventually sent out quartets on tour, each man representing one part of the four-part harmony settings, to promote both the singing and their book. This is the origin of modern gospel quartets. "Singings" were popular. These were gatherings inside or outside church worship to sing these sacred songs.

Shape-note, also called Fasola (from the first three notes: fa, so, la), which are also, more recently, are called do, re, mi) has an old history, and may stretch back to the poor rural Protestant peoples of the Border Country in England and Ulster. Another line of research suggests that it first came to New England and then spread south. It became visible to history with the publication of song-books, the most famous being The Sacred Harp, a commercial publication that became extremely popular, and which gave its name to this style of singing. It had many editions. The publishing company did much to spread the habit of shape-note singing, for this increased their own sales. They eventually sent out quartets on tour, each man representing one part of the four-part harmony settings, to promote both the singing and their book. This is the origin of modern gospel quartets. "Singings" were popular. These were gatherings inside or outside church worship to sing these sacred songs.

148 Jefferson (opening line: "Glorious things of Thee are spoken"), sung by the Ireland Sacred Harp Convention:

I haven't included the first part, as each song is usually "sounded" using the names of the notes instead of words to get everyone on time and in rhythm, and then they will sing the actual words.

I myself visited a small shape-note Singing in London UK, just to experience it, and I can attest that it is thrilling and moving.

268T "Restoration" (YouTube), sung by the Texas Sacred Harp Singers, will give you some sense of what it is like to sing Sacred Harp.

See more links to this music in my Discography.

The fly brush that Lorimer has constructed to shoo the flies away from the dining table was a real thing, and he mentions that he got the idea from another family. This family was the Walker Sisters, and this book about them is a good short guide of their house, which is still standing, and has photos of its interior.

Tobacco was grown at reasonably high elevations in the Smokies, although it would never have been of the best quality. The Fitch farm is within a micro-climate, but even so, their tobacco was for their own use and to swap or sell to neighbours, as it wasn't fit for major tobacco purchasers.

The music in the tobacco shed

In the tobacco shed, Airey plays the seventh of Telemann's Fantasias for solo violin. My favourite version is by Arthur Grumiaux, because of his precise, perfect feeling for the music.

Telemann: Fantasia for Solo Violin, no. 7, played by Arthur Grumiaux:

Here also is another version for your listening pleasure: nicely played by Tessa Lark (YouTube)

Airey's next pieces are short, the caprices by Rode. She plays 2, 8, 17, 18, 21 and 24. Not many of these are online, so I hope these two give you a taste of Rode's caprices, which I like far more than Paganini's.

Rode: Caprice no. 2, op 22, played by Axel Strauss:

Rode: Caprice no. 8, op 22, played by Steven Staryk:

After playing these Rode caprices, she plays the violin's part of the third movement of Geminiani's C minor sonata. If you can, tune out the piano and just listen to the violin.

Geminiani: Sonata in C minor for violin and continuo, played by Philippe Hirschhorn:

(By the way, of course Airey knows the entire sonata; she has, however, only played it with her teacher's violin accompaniment.)

Finally, Airey plays all of Bach's Second Sonata for solo violin. There are many performances of this online, including Grumiaux's: so I give you his: Bach: Second Sonata (YouTube). Flawless intonation! However, I can't stop myself from giving you this treat, the final piece from it, right here, because you need this in your life:

Bach: Sonata No. 2 for solo violin BWV 1003: (4) Allegro, played by Arthur Grumiaux:

Cecilia and Airey then listen to Mozart's fourth concerto for violin and orchestra. Below this box I have more information about the phonograph Cecilia has brought to introduce Airey to this and other music. Here, Mozart would have been on about ten to fourteen shellac records. You don't have to suffer the interruptions Airey endured, for here is the whole concerto played and conducted by David Oistrakh (YouTube)

If you don't want to go to YouTube, here is the first movement. This is a brisk, modern approach, but I like it very much (also, a live recording):

Mozart: Violin Concerto no. 4 K218, first movement: Allegro, played by Christian Tetzlaff (recorded 2020):

When Cecilia tries to persuade Airey to accept a career in concert music, and Airey resists, Cecilia challenges her, and Airey plays Paganini's caprice no. 10 as her reply. Paganini is technically more than tough to play, and I am not sure it is worth the effort, but there's no denying that it needs a superlative violinist to pull off his caprices. Have a listen to this blisteringly fast version:

Paganini: Caprice no. 10 in G minor, op. 10, played by Shlomo Mintz:

Airey follows this bravura performance with Veracini's Largo. Again, this is normally played with a keyboard accompanying it, which Airey has never done, playing only the violin part, so do your best to hear a violin by itself here:

Veracini: Largo, played by David Nadien:

Once Cecilia is successful in her persuasions, the two women play and replay Beethoven's sonata for violin and piano in C minor, opus 30, no. 2. I've chosen this version, although it is played a little slower than the version Airey heard, as music tended to be played faster in the early 20th century, because in this video Anne-Sophie Mutter is clearly the star performer, rather than the pianist, which is just how Airey would like it. Beethoven: Sonata for piano and violin op. 30, no 2 played by Anne-Sophie Mutter (YouTube).

All the music Airey hears is played on Cecilia's old Columbia Grafonola "50," with a brand name of "Favorite." It was one of the popular record-players of the early 20th century. It was heavy, but portable, had louvres in the front that opened to be the speaker, and required a new needle for every play of one side of a record. Wind-up phonographs were manufactured, at least in the UK, right up to the 1950s, and this interesting video of an acoustic wind-up (YouTube) shows pretty much how a Grafonola worked, and how it sounded. The first six minutes contain all you need to see, although he shows the brake about minute 14:00. The whole video is really interesting. Another bonus is that he first plays a violin recording! You can still buy Grafonolas second-hand. The Howison family had relegated their old Grafonola first to the children's use, and from there to the attic, for they had bought a spanking-new Victrola, the most popular record-player not only at the time of my story, but long afterwards. The Howisons' was a cabinet model, not portable, and had far better sound. A history of the Victrola, should you want to know more.

All the music Airey hears is played on Cecilia's old Columbia Grafonola "50," with a brand name of "Favorite." It was one of the popular record-players of the early 20th century. It was heavy, but portable, had louvres in the front that opened to be the speaker, and required a new needle for every play of one side of a record. Wind-up phonographs were manufactured, at least in the UK, right up to the 1950s, and this interesting video of an acoustic wind-up (YouTube) shows pretty much how a Grafonola worked, and how it sounded. The first six minutes contain all you need to see, although he shows the brake about minute 14:00. The whole video is really interesting. Another bonus is that he first plays a violin recording! You can still buy Grafonolas second-hand. The Howison family had relegated their old Grafonola first to the children's use, and from there to the attic, for they had bought a spanking-new Victrola, the most popular record-player not only at the time of my story, but long afterwards. The Howisons' was a cabinet model, not portable, and had far better sound. A history of the Victrola, should you want to know more.

The violinist Maud Powell is mentioned in passing. I have much more on this great American in my discography.

Cecilia says to Airey, to illustrate her commitment to finding Airey a career in concert music: "I will not cease from endless fight, nor will my sword sleep in my hand", which is a quotation from the poem Jerusalem by William Blake. This poem reverberates through the story, with other lines referred to or quoted. Read the entire short poem.

Chapter Three

Airey and her little sister Poly have gone around the farmhouse finding photos of Cecilia and her family in the newspapers the Fitches have used as wallpaper. The effect, as you can see, is surprisingly bright. It also serves as a bit of insulation. The sheets of newsprint on the walls were pasted in every direction. I have photographs of houses similarly wallpapered from as far north as the Canadian prairies, and I myself was once in an old shack of a place, lived in by an old wreck of a man, high in the Canadian Rockies, whose walls were similarly papered with pages from magazines, stuck every which way over all the walls. I found myself catching sight of celebrities at every angle, including upside down.

Airey and her little sister Poly have gone around the farmhouse finding photos of Cecilia and her family in the newspapers the Fitches have used as wallpaper. The effect, as you can see, is surprisingly bright. It also serves as a bit of insulation. The sheets of newsprint on the walls were pasted in every direction. I have photographs of houses similarly wallpapered from as far north as the Canadian prairies, and I myself was once in an old shack of a place, lived in by an old wreck of a man, high in the Canadian Rockies, whose walls were similarly papered with pages from magazines, stuck every which way over all the walls. I found myself catching sight of celebrities at every angle, including upside down.

The Beethoven sonata Cecilia and Airey work through on the front porch is the same as they listened to on records in the tobacco shed, the Sonata for violin and piano in C minor, no. 2, op, 30. Airey then teaches herself, from sheet music, Dvořák's Sonatina for violin and piano, op. 100, a charming and fun four-part piece that he wrote for his (very musical) children, based on American melodies and songs, especially African-American melodies, which he found particularly compelling during his stay in the United States. I particularly like this relaxed, delightful performance of the Sonatina (YouTube) — so suitable for a performance on a farmhouse porch.

Airey refers to the fecundity of her mountain home with a mention of Gabriel's Trump, which is from the Sacred Harp song 72t, Weary Soul. Cecilia and Airey then discuss the coming of the national park, which would in 1931 already have seen most of the farms already bought up by either the Tennessee or North Carolina state governments in preparation for becoming a federal park.

More about the National Park

In the early 20th century, a group of interests converged, people we would now call environmentalists who wanted to preserve an ecological area of outstanding beauty from the depredations of loggers, whose standard operating mode was a ruthless clear cutting, those desiring a national park in the east (all those already established were in the west), and local interests both in North Carolina and Tennessee, who saw the benefits in a tourist industry to a region that had few other sources of wealth.

In the early 20th century, a group of interests converged, people we would now call environmentalists who wanted to preserve an ecological area of outstanding beauty from the depredations of loggers, whose standard operating mode was a ruthless clear cutting, those desiring a national park in the east (all those already established were in the west), and local interests both in North Carolina and Tennessee, who saw the benefits in a tourist industry to a region that had few other sources of wealth.

The local interests kicked things off in the mid-1920s. Unlike in the west, the proposed boundaries of the new park contained farms and other lands owned by logging companies, all of whom would have to be bought out. This entailed much work persuading the states of Tennessee and North Carolina to find funds, and much pressure on the federal government to do the same. The activists preferred to buy interests out than to force eminent domain, but from the writings of those I have read, very little thought was given to those who had settled the area for several generations and who had emotional bonds to the land, and that thought was mostly dismissive. The collected memories of those farmers bought out or removed show that the blow was a heavy one. The Cherokee who lived in the area were, of course, well used to the United States deciding that their land and homes were more urgently needed by other people.

The process of buying up land in the area of the proposed park took many years. Logging companies, such as the Little River Lumber Company, were paid very handsomely, and were even permitted to keep up some logging into the late 1940s. Eventually they removed their railroads and settlements, having done themselves proud. Farmers' profits varied, and there was no consistency, some getting a very good price per acre, some not. A few farmers, mostly elderly, were allowed to lease their own land for the length of their lives.

The park having been authorised by the U.S. Congress in 1926, it was finally dedicated by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940, although a park Superintendent was appointed in January 1931, based in Maryville who, with two rangers appointed later, enforced the park rules both on visitors and the people who had always been living there. By 1940, the farming communities had been cleared off, the remaining logging industry was winding down, and the park began its boom. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park became, and remains, the most popular, most visited park in the USA. Where there were villages and communities, the modern buildings were destroyed and only a mythological landscape of log cabins and emptiness was preserved. The picture of the past life in the coves and valleys of the Great Smoky Mountains, most typified by Cades Cove, that beautiful falsehood, has obliterated the actual lives of those, indigenous and incomers, who lived in and loved these mountains before it was given to the hikers, campers, and car tourists.

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park became, and remains, the most popular, most visited park in the USA. Where there were villages and communities, the modern buildings were destroyed and only a mythological landscape of log cabins and emptiness was preserved. The picture of the past life in the coves and valleys of the Great Smoky Mountains, most typified by Cades Cove, that beautiful falsehood, has obliterated the actual lives of those, indigenous and incomers, who lived in and loved these mountains before it was given to the hikers, campers, and car tourists.

Sadly for the park, adjacent mining and other polluting industries nearby, plant disease, and climate change, have wrought havoc. This unique biosphere is seeing one species after another giving up. I visited the park twice, and was startled by the mist of death that seems to permeate so much of this astonishingly lovely and majestic mountain area.

The rain comes and goes, and Airey takes Cecilia along the stream that runs past the farmhouse up into the woods. A huge rock sticks out over the stream, wedged at an angle in the slope of the bank, and beneath is a small beach just large enough for two people. They lie there and watch the reflections of sunlight from the water on the rock. When I visited The Great Smoky Mountains National Park, I saw this water-reflected sunlight in many, many places and was enchanted by it. I knew that it would be special to Airey. I climbed down to the stream that flows through Elkmont, some distance below the camping area, sat on a boulder in the middle of the stream, and just watched the light and the water and the little waterfalls dropping from rock to rock, and the sounds of insects and birds. The photo here is one I took, but of course no one can capture the sense of the movement of the trees and the water and the light. Airey quotes Psalm 29:3 and speaks of having transcendent moments while she was playing music such as Bach or playing:

The rain comes and goes, and Airey takes Cecilia along the stream that runs past the farmhouse up into the woods. A huge rock sticks out over the stream, wedged at an angle in the slope of the bank, and beneath is a small beach just large enough for two people. They lie there and watch the reflections of sunlight from the water on the rock. When I visited The Great Smoky Mountains National Park, I saw this water-reflected sunlight in many, many places and was enchanted by it. I knew that it would be special to Airey. I climbed down to the stream that flows through Elkmont, some distance below the camping area, sat on a boulder in the middle of the stream, and just watched the light and the water and the little waterfalls dropping from rock to rock, and the sounds of insects and birds. The photo here is one I took, but of course no one can capture the sense of the movement of the trees and the water and the light. Airey quotes Psalm 29:3 and speaks of having transcendent moments while she was playing music such as Bach or playing:

Louisburg Blues. Recorded by Uncle Bunt Stephens in 1926, which explains the quality of the sound; the quality of his playing is superb.

or playing

Stardust, by Hoagy Carmichael. Played on the violin by Dan Cassidy (with guitar accompaniment).

They discuss their hopes for their futures. Cecilia talks about a book her great-aunt Ruth used to teach herself about the stock market. The book is Men and Mysteries of Wall Street by James Medbery (1870) and I offer it as a PDF download, because it is out of copyright, if you would like to read it. Its dry tone is in contrast to so many other books of that time gushing about the glowing opportunities of Wall Street.

After her visit to Airey, Cecilia, in a gown by the French designer Vionnet, goes to a private music recital. It has been arranged by her brother Tom, who organises a number of them throughout the year. His recitals are usually in a public venue, such as a local hotel, but tonight it is a private recital, by invitation only. Cecilia's sister Phyllis, the wife of an important political party bigwig of their state, is hosting it in her home as a favour to her family. Phyllis lives in the city of Charleville. Jean du Charleville (also known as Charles Charleville) was an early fur-trader who established a trading post in what is now Tennessee in 1710, and I thought he should be honoured with a city.

After her visit to Airey, Cecilia, in a gown by the French designer Vionnet, goes to a private music recital. It has been arranged by her brother Tom, who organises a number of them throughout the year. His recitals are usually in a public venue, such as a local hotel, but tonight it is a private recital, by invitation only. Cecilia's sister Phyllis, the wife of an important political party bigwig of their state, is hosting it in her home as a favour to her family. Phyllis lives in the city of Charleville. Jean du Charleville (also known as Charles Charleville) was an early fur-trader who established a trading post in what is now Tennessee in 1710, and I thought he should be honoured with a city.

The performers at the recital are Dr Neihoff, a violinist with a high reputation in his dual careers as concertmaster and leader of a quartet, and Cecilia's former music teacher, a well-known, but now retired, pianist, Mrs Vernelle, whom Cecilia has mentioned to Airey as an example of a (then) single woman who achieved a distinguished professional solo career.

The music played at the recital

The pieces Dr Neihoff and Mrs Vernelle play in the first half of the concert are: Albeniz's Malaguena: listen to a slowish version by Michel Schwalbé (YouTube); Paganini's La Campanella, and since it is by Paganini, it's full of tricky bits — watch a chirpy version by Clara-Jumi Kang (YouTube) (you can see the playing close up); the Rondo from Mozart's Serenade No. 7 (K. 250), called the Haffner, and here played limpidly by Itzak Perlman (YouTube); Faure's Sicilienne, beautifully played by Alban Beikircher (YouTube); and Rachmaninov's Dance Hongroise here excitingly played (if none too clearly recorded) by Ahmed Pyshtiyev (YouTube), which certainly serves as an impressive end to part one of the recital.

After an intermission where Cecilia is frustrated in her goal of Dr Neihoff's help, the recital continues. The pieces are (again all links are to YouTube): Schubert's Violin Sonata No. 1 in D major, a longish piece chosen because their audience now can't sneak out, here played by Szymon Goldberg. The climax of the recital is Vitali's Chaconne, another long-ish piece, here played by the legendary Nathan Milstein:

Vitali: Chaconne in G minor, played by Nathan Milstein:

The recital closes with Wieniawski's Étude Caprice Op.18, No.4, played in fiery style by James Ehnes.

After the recital, Cecilia goes off to a party with her friend Patmore. In his car, given that he is a little the worse for wear, she refers to the Volstead Act, which introduced Prohibition in 1919. After the party, trying to be kind to him, she refers to Proverbs 12:4: A virtuous woman is a crown to her husband and also to the commonly-held idea that a man ennobles his wife with his love and she sees his love as her most treasured possession, indeed, as her life's crown.

Chapter Four

Cecilia and her brother Tom have a difficult conversation, in which he refers to himself as a "remittance man." This was usually some sort of scapegrace or failure whom the family shipped off to somewhere far, far away and who was given an allowance (remittance) to stay there. It is a British term, and remittance men tended to go to the Canadian west, British South Africa, Australia, or New Zealand. Some enjoyed a life of polo or hunting or drinking, others made something of themselves. Tom fancies himself as both a Southern and an English gentleman, so naturally he would like the idea of being the son of a nobleman cast off to the frontier. Even though the frontier was Hollywood.

At the end of their conversation, Tom, who is a good musician and very knowledgeable, sits at the piano to help Cecilia, who is struggling to teach herself Réminiscences de Don Juan by Franz Liszt. It's a challenging piece, as Liszt was the Paganini of the piano and always writing pieces that only he could master. I can't say it is one of my favourite works, as I don't like Liszt. Here is one to listen to that shows the sheet music (YouTube), so you can see what Cecilia is up against.

The next morning, Cecilia heads up to the Fitch farm, where she hopes to have Airey to herself. Instead she finds two strangers, who have come from the Siffville Settlement.

About Settlements

Settlements were an exercise in social welfare, either reaching out to the slums or to "backward" rural communities. The people involved wanted to help lift people out of destitution and the debility of ignorance by assisting with education, health, and sometimes religious exhortation. Begun either by Christians seeking to express their faith in practical ways, or by Progressives, the settlements would often be a building or meeting house, where a programme of outreach was run, consisting of good works, finding or creating employment, establishing schools for children or adults or both, and (if religious in origin) preaching and Bible study. All very worthy, and indeed in the slums of English and American cities, Hull House in Chicago being the most famous example, they had their successes.

Settlements were an exercise in social welfare, either reaching out to the slums or to "backward" rural communities. The people involved wanted to help lift people out of destitution and the debility of ignorance by assisting with education, health, and sometimes religious exhortation. Begun either by Christians seeking to express their faith in practical ways, or by Progressives, the settlements would often be a building or meeting house, where a programme of outreach was run, consisting of good works, finding or creating employment, establishing schools for children or adults or both, and (if religious in origin) preaching and Bible study. All very worthy, and indeed in the slums of English and American cities, Hull House in Chicago being the most famous example, they had their successes.

However, and you knew there would be a "however," these settlements were usually run by the better off (who had the liberty to do so) to save the poor as much from themselves as from their disadvantages. Class assumptions, class privilege, prejudice, and all that goes with these, saw poor families hectored, chivvied, talked down to, and forced to fit whatever fantasies the people in charge had of them. In the case of the poor families in the Appalachias and Great Smoky Mountains, this meant being taken as living fossils of pioneers, as if they had been trapped in a time warp.

Mountain people were taught the "ancient" crafts the organisers fancied their "Elizabethan" pioneer forefathers had originally brought over to the New World and that their shiftless descendants has somehow forgotten, and should resume, as it would better fit their "spirit" or "primitive dignity" or other fustian. I cite two books that show the impact of these settlements in Appalachian communities. Settlements in the mountains often assumed that mountain people were dissipated, ignorant and, above all, lazy, that is, the stereotype of the hillbilly. I could not help but rage at the quote from one mountain woman forced to do Settlement-approved work: "I get up as early as I can and work as hard as I can" — yes, this is one of the lazy hill-folks, who earned a pittance from her weaving, sold by the settlement. When the mountaineers rebelled against being exploited by the people who came to "help" them, they were called ungrateful. You can hear my teeth grinding from there.

I offer a recipe for cat head biscuits, which Airey's mother was preparing before the Siffville Settlement people arrived. Mrs Grigg quotes the Bible, when referring to her children's previous illnesses. It's Leviticus 13:45. Later, she says glitt'ring bride, she is quoting from a fasola (Sacred Harp) song 170 Exhilaration. The Siffville people also quote the Bible, King James Version: 2 Peter 3:10,1 Corinthians 15:52, and Proverbs 29:15. We find out the origin of Airey's sister Poly's name. I give you the cover of a movie magazine, of the type Poly loves, dated March 1923, when Poly would have been in the womb.

I offer a recipe for cat head biscuits, which Airey's mother was preparing before the Siffville Settlement people arrived. Mrs Grigg quotes the Bible, when referring to her children's previous illnesses. It's Leviticus 13:45. Later, she says glitt'ring bride, she is quoting from a fasola (Sacred Harp) song 170 Exhilaration. The Siffville people also quote the Bible, King James Version: 2 Peter 3:10,1 Corinthians 15:52, and Proverbs 29:15. We find out the origin of Airey's sister Poly's name. I give you the cover of a movie magazine, of the type Poly loves, dated March 1923, when Poly would have been in the womb.

When Airey's sister Merit is about to leave, Cecilia gives her a gift of money and a tiny bottle of Worth perfume. Worth was the first of the great fashion houses. French, of course. Cecilia's small bottle is a gift from her mother, who is a little old-fashioned in her tastes, and who also has the money to import this for Cecilia (and also the hat Cecilia is wearing on this visit, imported from Italy). The Howisons are not struggling, even in these first deep years of the depression. Cecilia's is Eau de Cologne à L'Œillet, created by Worth in 1929, and is mostly floral, with a hint of spice. A modern, less good, version is still available to buy. (Pretty much all recipes of classic perfumes have been modified, because the original ingredients were expensive, and tastes have changed.)

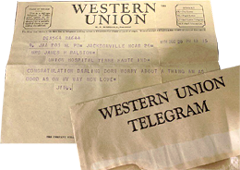

Back at home, unhappy and (rightly) writhing under her finely-tuned sense of shame, Cecilia plays Brahms, first his Ballades (try these four pieces played by Krystian Zimerman (YouTube), and I think you'll agree that these are good for a troubled spirit), then his Intermezzi (Brahms: Intermezzi have a listen (YouTube), and later through the weeks she plays the rest of his works for solo piano, also Bach, also anything she can think of to play to distract herself. She is playing Schumann when her sister-in-law Rosamund comes in to talk to her. My favourite pianist is here playing one set of Schumann's works for solo piano: Schumann: Waldszenen played by Wilhelm Kempff (YouTube), which is about the forest. And then that second-swiftest social media channel, the telegram, changes her plans and tempts her to do what she knows she should not.

Back at home, unhappy and (rightly) writhing under her finely-tuned sense of shame, Cecilia plays Brahms, first his Ballades (try these four pieces played by Krystian Zimerman (YouTube), and I think you'll agree that these are good for a troubled spirit), then his Intermezzi (Brahms: Intermezzi have a listen (YouTube), and later through the weeks she plays the rest of his works for solo piano, also Bach, also anything she can think of to play to distract herself. She is playing Schumann when her sister-in-law Rosamund comes in to talk to her. My favourite pianist is here playing one set of Schumann's works for solo piano: Schumann: Waldszenen played by Wilhelm Kempff (YouTube), which is about the forest. And then that second-swiftest social media channel, the telegram, changes her plans and tempts her to do what she knows she should not.

Chapter Five

Dr Neihoff and his wife, driven by Mr Vernelle, with Mrs Vernelle along to assist and to help judge Airey's talent, meet Cecilia at a country hotel in their Ford Model T touring car. The car is six years old, as it is the 1926 model (see image); the Vernelles are not rich. Airey has prepared a number of pieces to play for these, her distinguished visitors.

Dr Neihoff and his wife, driven by Mr Vernelle, with Mrs Vernelle along to assist and to help judge Airey's talent, meet Cecilia at a country hotel in their Ford Model T touring car. The car is six years old, as it is the 1926 model (see image); the Vernelles are not rich. Airey has prepared a number of pieces to play for these, her distinguished visitors.

The music of the audition

The first piece of music Airey has prepared for this audition is the Presto from Bach's Sonata No. 1 for solo violin.

Bach: Presto from Sonata 1 for solo Violin, played by Thomas Zehetmair:

This is a good choice to demonstrate skill, interpretation, intonation, control, everything a first-rank violinist should have. Airey then plays as much of the slow movement from Tchaikovsky's violin concerto as a solo violin can play. Luckily, it is mostly one connected piece, except for a bit where the orchestra plays. In the full piece, the orchestra finishes off the movement. Airey heard it for the first time on one of the sets of records Cecilia brought for her, played by Fritz Kreisler, and here is the exact recording, which was slightly rewritten to give it an ending that works for this stand-alone arrangement for violin and piano.

Tchaikovsky: Canzonetta (abridged), from Violin Concerto in D Major. Played by Fritz Kreisler in 1924:

However, Airey would have ended the violin part properly, simply hanging on its last note, given that she would have seen it (thanks to Cecilia) in the sheet music of the concerto. If you can ignore the entire orchestra, Airey's version would have sounded something like Itzhak Perlman's (YouTube). (I should just mention that I had Airey choose the Tchaikovsky because she wanted to show that she could learn a new piece quickly, and so chose something new to her, and newer in time than anything she grew up playing. Tchaikovsky's violin concerto is by far my least favourite. I repeatedly say so in my Violin Discography.)

I don't name them, but Airey is using her teacher's violin, one made by Alexandre Delanoy [1900] (Mr Broeggen traded down to this from a Justin Derazey [1880], as he traded down his talent throughout his life). Dr Neihoff plays a violin made by Santo Serafin [1699-c1758], which he originally thought was an Amati. Airey's bow (also inherited from Mr Broeggen) is by Joseph Vigneron (Broeggen traded down to this from a Jean-Joseph Martin [1880]), Dr Neihoff's bow is by Charles Nicolas Bazin, after Lupot.

Airey mentions her preference for a minimal vibrato. You might be interested to watch this fun but informative video by TwoSet Violin on the changing violin styles in the last 60 years (YouTube). They cover vibrato, gut and steel strings, historically-informed playing, and more (but it's painful to hear that 1962 is "olden tymes").

Dr Neihoff asks Airey to play the Adagio from the same Sonata No. 1 by Bach. Hear it played by Augustin Handelin (YouTube). Mr Vernelle is, meanwhile, putting together his wife's clavichord, which was an old keyboard instrument predating the piano and reproduced in the 19th and 20th centuries for players interested in older styles of instrument in the same way harpsichords were and are reproduced. Mrs Vernelle finds it a useful travelling piano for just this sort of occasion, i.e. when she has been asked to travel somewhere to audition some aspiring musician. (Click on the image of the clavichord to hear and see a clavichord being played (YouTube). To my ears, it's half-way between a harpsichord and a classical guitar.) The piece of music Dr Neihoff teaches Airey is Josef Suk's Appassionato. I prefer Suk's violinist son's version.

Dr Neihoff asks Airey to play the Adagio from the same Sonata No. 1 by Bach. Hear it played by Augustin Handelin (YouTube). Mr Vernelle is, meanwhile, putting together his wife's clavichord, which was an old keyboard instrument predating the piano and reproduced in the 19th and 20th centuries for players interested in older styles of instrument in the same way harpsichords were and are reproduced. Mrs Vernelle finds it a useful travelling piano for just this sort of occasion, i.e. when she has been asked to travel somewhere to audition some aspiring musician. (Click on the image of the clavichord to hear and see a clavichord being played (YouTube). To my ears, it's half-way between a harpsichord and a classical guitar.) The piece of music Dr Neihoff teaches Airey is Josef Suk's Appassionato. I prefer Suk's violinist son's version.

Suk: Appassionato, from Four Pieces op. 17, no. 2. Played by Josef Suk (Jr):

You might also want to listen to this performance of it by Augustin Hamelich (YouTube) as it is very close, though a little slower and a little sweeter.

While Cecilia is sitting outside with Mrs Neihoff, and then being distracted with Poly and Jabez, she hears Airey playing Paganini's 16th Caprice (here played by Claudio Accardo (YouTube), as well as his 13th, 5th and 6th. She also hears, but I do not name, several études by Kreutzer. There are none to be found online, so I offer them here:

Kreutzer: étude no. 2, to teach détaché. Played by Steven Staryk.

Kreutzer: étude no. 8, to hone portato. Played by Steven Staryk.

Kreutzer: étude no. 13, which focuses on bowing. Played by Cihat Aşkin.

Kreutzer: étude no. 37, which trains off-the-beat phrasing. Played by Cihat Aşkin.

After Cecilia has to leave her guests to attend to Poly and Jabez, she hears Airey playing Sarasate's Capricho Vasco, also known as the Caprice Basque (played by Antal Zalai (YouTube) with piano accompaniment; block that out).

When Airey challenges everyone to listen to her, she plays Vitali's Chaconne, the piece played, although she doesn't know it, by Dr Neihoff and Mrs Vernelle at their recital in Charleville some time before, when Cecilia was in the audience. The Chaconne is written for keyboard accompaniment, but I did find one—only one—example of the violin part played solo, and I hope it gives an idea of what the people in the farmhouse heard that day:

Vitali: Chaconne in G minor, played by Stepan Grystsay:

It is this that turns the tide for Airey.

The man the Fitches called Mr Brewken was from the Netherlands and his name, as Airey and Cecilia learn, was Kees Broeggen. It is hard to pronounce. "Kays" is pretty close for his first name. His surname starts as "broo," then the Dutch "gg" which is sort of like the "ch" in the Scottish word "loch" but much more gargly, and finally the "n." Faced with that, it's no wonder that the Fitches and everyone else went for their own approximation. Kees Broeggen came to the USA on his long slide downhill to an alcoholic death, hoping to save himself with a fresh start as concertmaster of the Melita Symphony Orchestra. Melita is sort of, kind of, Toledo, Ohio. All these cities in what is now the Rust Belt were centres of vibrant cultures as well as industry, and the mark of a successful city was, among other things, an orchestra (read Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis [1922] to see what I mean).

I would like to quote Gerald Moore (p. 52 and p. 140) at this point, He is speaking of Renée Chemet, a violinist with whom he worked: "This awareness of one's own value is a regal quality attaching itself to the really great and bears no relation whatsoever to the vanity with which the mediocrity sometimes preens himself.... It does not detract one jot from their humility as seekers after the truth or make them less human to their friends. It is an added dignity grafted on to the personality and acts as a protection."

Cecilia takes the visitors down to the main road and returns to the farm. She and Airey talk about Airey's future. Airey is full of confidence, and quotes from the King James Bible: 1 Chronicles 17:27. Cecilia knows Airey might well become a millionaire. At this time, Yehudi Menuhin earned well over about $1000 a concert, and $1000 in 1931 works out to roughly $17,500 today. Airey mentions that Dr Neihoff praised her spiccato. What spiccato is (YouTube). Airey puts together a quick supper of dry pone in hot cream. Pone, or corn pone, is similar to cornbread, but made as patties. This site gives information as well as a recipe. After the meal, when Airey and Cecilia are talking on the porch, Cecilia thinks about caryatids. These are pillars carved into the shape of women that hold up a roof.

Cecilia takes the visitors down to the main road and returns to the farm. She and Airey talk about Airey's future. Airey is full of confidence, and quotes from the King James Bible: 1 Chronicles 17:27. Cecilia knows Airey might well become a millionaire. At this time, Yehudi Menuhin earned well over about $1000 a concert, and $1000 in 1931 works out to roughly $17,500 today. Airey mentions that Dr Neihoff praised her spiccato. What spiccato is (YouTube). Airey puts together a quick supper of dry pone in hot cream. Pone, or corn pone, is similar to cornbread, but made as patties. This site gives information as well as a recipe. After the meal, when Airey and Cecilia are talking on the porch, Cecilia thinks about caryatids. These are pillars carved into the shape of women that hold up a roof.

Cecilia is able to wash in warm water, thanks to the cook stove.

More about cook stoves

Kitchen ranges were cast iron, the more expensive having nickel-plating on handles and on the fancy cast decorations. These stoves served many functions, as a stove-top, with usually four or six burners, cast-iron discs that lifted off if you wanted to put your pan directly on the flame. The oven below would be big by the standards of the day, small by ours. Some large ranges would have one large oven and one or two smaller ones, some meant for bread baking, some for keeping things warm, all depending on their proximity to the fire. The fire chamber or fire box, for wood or coal, would have openings to let in air and dampeners to lower the flames, to allow you to adjust the fire to your needs or to keep the coals alive overnight.

Kitchen ranges were cast iron, the more expensive having nickel-plating on handles and on the fancy cast decorations. These stoves served many functions, as a stove-top, with usually four or six burners, cast-iron discs that lifted off if you wanted to put your pan directly on the flame. The oven below would be big by the standards of the day, small by ours. Some large ranges would have one large oven and one or two smaller ones, some meant for bread baking, some for keeping things warm, all depending on their proximity to the fire. The fire chamber or fire box, for wood or coal, would have openings to let in air and dampeners to lower the flames, to allow you to adjust the fire to your needs or to keep the coals alive overnight.

Most stoves had a water reservoir, lined with porcelain, that provided hot water via a tap. Fancier stoves would have an upper cabinet for keeping things warm, such as plates, that took advantage of the heat going up the chimney pipe.

These stoves were the engines of the kitchen, with hot washing water (for clothes, dishes, and people), food preparation areas, different levels of heat for cooking, places to hang wet towels or clothing in the winter, while giving general warmth and having a lot of shining nickel or polished cast-iron curlicues to show off and to indicate that the housewife had been respected enough by her husband to be given such an impressive monster.

In Mrs. Grigg's case, her first husband installed a new cook stove when they moved into the house as a newly-married couple, and hers signalled a definite level of wealth at the time. It would have been much like the image here, that is, not very fancy at all. By 1931, it was very old-fashioned indeed, but nobody in Fittes Cove would have had an electric one. The more up-to-date might have ranges with enamelled doors and no curlicues.

My grandparents had a cottage on a lake in lower Quebec (the Eastern Townships) and they had a big range dating from the 1890s. It was used for general heat and as a fireplace, when its front doors were open, for the cheer of the flames, but we'd often cook on the top if the tiny propane oven in the kitchen annexe was over-full. I have good memories of stoking the fire-box with kindling in the mornings.

Chapter Six

Cecilia wakes to see a pitcher and basin. The pitcher would be filled with hot water. The basin serves as the sink. You can keep adding hot, clean water, and then the basin of soapy water can be disposed of. Johnnycake is on the menu for breakfast. It is a pancake made from cornmeal. This traditional recipe (although for certain no Fitch calls them "Rhode Island") is extremely simple to make, but if you think Airey can achieve these golden glories, you should think again.

Cecilia wakes to see a pitcher and basin. The pitcher would be filled with hot water. The basin serves as the sink. You can keep adding hot, clean water, and then the basin of soapy water can be disposed of. Johnnycake is on the menu for breakfast. It is a pancake made from cornmeal. This traditional recipe (although for certain no Fitch calls them "Rhode Island") is extremely simple to make, but if you think Airey can achieve these golden glories, you should think again.

Poly, as she has done throughout, talks about movie magazines. There were many titles, all carefully managed by the press and publicity offices of the Hollywood studios, with very little salacious material, unless the studios thought that might be in their interest. A few of the less savoury ones did manage to dish up dirt, and actors' lives could be and were ruined even by rumours. Some, such as William Haines, took a principled stand, but others were destroyed. The covers here are from March, May and June 1931, that is, ones Poly actually has in her possession (gifts from neighbours), although I give her a fictional favourite.